Excerpt from article by Michael Blanding originally published in Forbes

Most governments aren’t subtle when they want citizens to do something. The United States spends close to $1 billion annually on advertising—trying to convince citizens to do everything from taking flu prevention shots to reporting unattended suitcases at the airport. But now agencies are finding that subtle “nudges” can motivate behavior much better than ads, fines, or deadlines.

Nudges, or small changes to the context in which decisions are made, are the subject of a new analysis by Harvard Business School Associate Professor John Beshears and colleagues, recently published in the journal Psychological Science. The paper, Should Governments Invest More in Nudges? answers its own question with a resounding “Yes.”

“We suspected that nudges on an impact-per-cost basis would be superior to traditional approaches such as a financial incentive or an educational campaign,” says Beshears. “But we were surprised to see the extent to which it is true.”

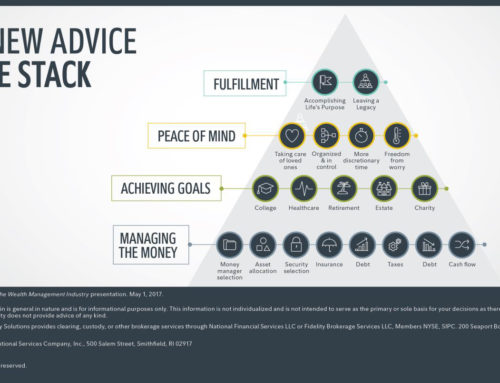

According to behavioral scientists, nudges are dollar for dollar a hugely cost-effective way of causing people to change behavior and do the kinds of things that government wants them to do, like save for retirement—which are both for the good of society and for their own good.

Here’s an example. On the first day of a new job, the paperwork is coming at you fast and furious, including a packet of information about how to sign up for the retirement savings plan. What is more likely to make you fill out the sign-up form, information about the importance of saving for your golden years or a deadline that requests you fill it out within 30 days? If you are like most of us, it’s the latter.“In the flurry of activity in starting a new job, it’s easy to say, ‘I’m going to fill it out later,’” says Beshears. “But then there is never a convenient time.” Providing a deadline, even one that isn’t strictly mandatory, cuts through the procrastination cycle, spurring employees to action.

Nudges are less expensive and more productive

According to their analysis, money spent on nudges can in some cases be more than 40 times more effective than the next most effective method, a dramatic result for governments dealing with scarce resources.